01. What Is a Superfund Site?

What Is a Superfund Site?

For centuries, dumping waste was largely unregulated in the United States. As a result, the improper management of industrial refuse at landfills, manufacturing sites and mines created thousands of contaminated sites across the country. These sites were contaminated with asbestos and other hazardous materials.

By the 1970s, these hazardous sites gained more attention as the public learned more about associated health risks.

New York’s 1978 Love Canal scandal is one of the most famous examples of a company dumping hazardous chemicals. Hundreds of families were evacuated due to tons of hazardous chemicals disposed of at the canal. This triggered a state of emergency, pushing the federal government to take action. Kentucky’s Valley of the Drums incident was another contributing factor to Congress moving forward and developing the Superfund law.

December 11, 1980, saw the enactment of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA). This law, informally known as Superfund, aimed to hold petroleum and chemical industries accountable. Congress set up a trust fund (also called the Superfund) using tax collected from relevant industries to clean up uncontrolled or abandoned hazardous sites.

The goals of the Superfund program are to:

- Protect environmental and public health by cleaning these sites

- Hold the companies responsible for the cleanup

- Potentially redevelop the sites for future use

02. Assessing Superfund Sites

How Does a Site Become a Superfund?

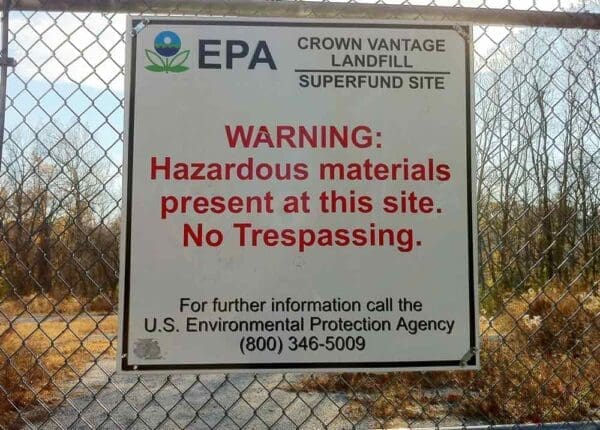

The first step to a site becoming a Superfund is awareness. The process starts with a notification to the EPA about a contamination-related concern at a particular site. The EPA then begins a process called Superfund site assessment, which ensures a standardized and compliant approach.

The first thing the EPA assesses is whether the site qualifies for further assessment. If it does, it’s placed on the National Priorities List (NPL). The NPL helps guide the EPA for what sites warrant further investigation. The next thing officials analyze is whether it requires immediate action, further investigation or deferral to different EPA programs. As of May 2021, there are 1,327 sites on the NPL, with an additional 43 proposed NPL sites.

Sites that are not put on the NPL stay with the state or local government but may be referred to other EPA cleanup programs as appropriate.

When it comes to asbestos sites, the eligibility assessment takes into account the potential health risks for land use now and in the future. The EPA uses a specific framework to investigate asbestos Superfund sites.

EPA’s Evaluation Process for Asbestos-Related Superfunds

There are five steps required to investigate if a site is eligible for EPA asbestos cleanup:

- A preliminary investigation takes place to see if any naturally occurring asbestos is present. Investigators assess the historical and current use of asbestos-containing materials at the site.

- Investigators determine how immediate the risk for airborne asbestos contamination is. Friable asbestos is particularly dangerous because it’s loose, and the fibers may easily become airborne. Investigators consider if the release of airborne fibers has already occurred, could occur with human activities or if a release is likely in the future.

- The EPA analyzes the likelihood of human asbestos exposure. Investigators consider the hazards associated with the current and future state of the site.

- The EPA conducts preliminary screening and sampling. This determines if the amount of asbestos exceeds safe levels.

- Samples are evaluated to determine how highly concentrated the contamination level of the site is. Officials compile a risk assessment based on their analysis.

- The EPA determines a response action or remediation. Investigators outline a long-term plan to fix the current problem and avoid future occurrences.

Once the above steps are complete, the EPA decides whether to take immediate action or add the site to its database as a non-priority for cleanup.

Resources for Mesothelioma Patients

03. EPA Asbestos Cleanup

EPA’s Cleanup of Asbestos-Contaminated Superfund Sites

After an asbestos-contaminated site is designated as a Superfund, the EPA must put a cleanup plan in place. The EPA’s primary aim is to protect the public’s health and ensure the environment is well-looked-after.

Cleanup plans will vary depending on the site’s needs, including the presence of other contaminants. During cleanup, the EPA and local governments will work to properly remove and dispose of asbestos and other contaminants at the site.

The timeline for cleaning Superfund sites varies significantly depending on a variety of factors. In 1997, the aim was to remediate all Superfund sites within five years. However, the extent of contamination, needed site monitoring and a variety of other issues mean it’s not always possible to meet this goal.

To maximize the effectiveness of the Superfund program, the EPA aims to:

- Encourage private investment

- Get local communities involved in and aware of the cleanup process

- Incentivize various parties to assist with the rehabilitation of contaminated sites

What Happens to an Asbestos Superfund Site After Cleanup?

After a site is cleaned, it needs to go through several more steps before it’s eligible for reuse. When cleanup is complete, the EPA verifies that it’s taken sufficient measures to ensure the long-term protection of the health of people and the environment.

To protect public health, the EPA takes the following actions after cleanup of an asbestos Superfund site:

- Develops plans for continued operation, maintenance and monitoring

- Creates long-term response actions, such as monitoring of impacted groundwater

- Sets institutional controls to minimize the potential for human exposure

- Conducts five-year reviews to evaluate the efficacy of cleanup efforts in protecting human and environmental health

Once satisfied the site is ready to return to safe and productive use, the EPA removes the Superfund site from the NPL. Before doing so, it provides a period for public comment and only moves forward with removal if it’s warranted.

04. Libby Asbestos Superfund

Libby Asbestos Superfund Site

One of the most well-known and largest asbestos Superfund sites is in Libby, Montana. The city used to have a large network of vermiculite mines. Vermiculite is a mineral that was used for insulation, potting soil and fertilizer. Vermiculite naturally occurs near asbestos, which led to contamination.

By the 1920s, the Zonolite Company started mining vermiculite in Libby. In 1963, W.R. Grace purchased the site. Vermiculite mining continued in Libby until the mine closed in 1990.

Some sources say Libby once produced around 80% of the world’s vermiculite. Unfortunately, the vermiculite mined in Libby contained tremolite-actinolite asbestos. This form of asbestos is highly friable and, therefore, highly dangerous. Residents and workers in Libby risked exposure and the development of asbestos-related diseases, including mesothelioma.

The public, media and local government reported concerns about the site in 1999. By 2000, the EPA began an investigation. The Libby mines were added to the NPL by 2002 and a cleanup plan was later approved. Cleanup efforts of asbestos at the site were completed in 2018. The levels of harmful airborne substances are now nearly 100,000 times lower than when the mines were in operation.

05. Ambler Asbestos Superfunds

Ambler Asbestos Superfund Sites

Ambler, Pennsylvania, features two sites that made the NPL: BoRit Asbestos Piles and Ambler Asbestos Piles. Both sites are the result of decades of improper waste disposal from local manufacturing plants.

Asbestos waste was dumped at these sites beginning in the 1930s. The asbestos piles created health hazards for those who worked and lived in Ambler. In the 1970s, residents began to realize the dangers of the asbestos waste areas.

Ambler Asbestos Piles was added to the NPL in 1986, with cleanup completed in 1993. It was removed from the NPL in 1996. The BoRit Asbestos Piles Superfund site was added to the NPL in 2009. The EPA completed remedial work at BoRit Asbestos Piles in 2018. Maintenance and security work at both sites is ongoing to ensure the future safety of the location.

06. Military Superfund Sites

Military Superfund Sites With Asbestos Contamination

Until the 1980s, branches of the United States military relied on asbestos. At the time, the mineral was considered a cheap, reliable way to provide heat and chemical resistance at bases, on ships and in equipment. Many military bases built before 1980 have become Superfund sites due to hazardous substances, such as asbestos.

George Air Force Base

Construction of the George Air Force Base in Victorville, California, took place during World War II. During this time, asbestos was often used in building materials and other products. As a result, asbestos and other contaminants used at the Air Force base contaminated the soil and groundwater. The site closed in 1992.

The EPA agreed to clean the base in 1990. Cleanup efforts are ongoing to address a groundwater plume, landfills and contaminated soil.

Pensacola Naval Air Station

Pensacola Naval Air Station is a 5,900-acre site in western Florida. The U.S. Navy began operations at the site in 1825 and is still active there. Throughout its history, asbestos and other contaminants were used in the construction of buildings at the air station. This use polluted the groundwater, soil and surface water.

The EPA placed it on the NPL in 1989. Cleanup of the site has been ongoing. The most recent cleanup plan in 2017 aims to clean up soil and groundwater in the location.

Naval Weapons Station Earle

The Naval Weapons Station Earle is a naval base in New Jersey with 27 sites. The Navy used this site in the 1940s, during a time when asbestos use was popular. Later EPA investigations found asbestos contamination in various buildings.

In 1990, the EPA added all 27 sites at Naval Weapons Station Earle to the NPL. Efforts to clean up this site are still in operation.

Curtis Bay Coast Guard Yard

Curtis Bay Coast Guard Yard is an active military facility in Baltimore, Maryland, that dates back to 1899. The site was used to design, construct and repair ships. Until the late 1970s, many ships were built with asbestos materials, such as insulation and boilers.

It became a Superfund site in 2002 due to early on-site incinerator activity and ship maintenance that contaminated the soil with asbestos and other substances. Between 2009 and 2013, cleanup was performed. Maintenance and operational activities are currently ongoing.

07. List of Asbestos Superfunds

Other Asbestos-Contaminated Superfund Sites

Until 1980 when asbestos became more regulated, many other industries frequently used the mineral. As a result, manufacturing facilities, shipyards, plants and other places have become Superfund Sites due to asbestos and other hazards. These asbestos-contaminated Superfund sites are in different stages of cleanup and remediation.

Tacoma Dry Dock Shipyard

Tacoma Dry Dock Shipyard in Washington is part of the Commencement Bay Superfund Site. The Superfund site consists of an active seaport and miles of the shoreline. Water, sediment and upland areas suffered from widespread contamination at the site, including from asbestos.

The former shipyard at Tacoma was added to EPA’s NPL in 1983. Resistance from local government led to delays. The site has now made it onto the list of former Superfund sites that are in reuse. However, some cleanup is still ongoing and the site continues to be monitored.

North Ridge Estates

North Ridge Estates in Oregon went onto the NPL in 2011 due to asbestos contamination from the 1940s. Military barracks buildings at the site were built with various asbestos materials. The site became contaminated with asbestos after the buildings were improperly demolished, releasing asbestos fibers into the air.

Between 2016 and 2018, the EPA worked on the cleanup of North Ridge Estates. The agency restored around 40 properties and disposed of 360,000 cubic yards of asbestos-contaminated material. It also planted more than 1,000 trees and resurfaced two roads. The site has been returned to productive use, but long-term monitoring will continue.

Fike Chemical, Inc.

The EPA identified Fike Chemical, Inc., a chemical processing plant in West Virginia, as a Superfund site in 1983. The site was added to the NPL due to contamination from asbestos and other chemicals. The cleanup took place between 1984 and 2001. Institutional controls, including zoning restrictions, are now in place. The EPA will conduct ongoing five-year reviews to prevent dangerous exposure at the site.

Over time, other asbestos-contaminated sites may be added to the EPA’s Superfund sites program. The EPA continues to discover and assess contaminated sites for cleanup. Asbestos Superfund sites currently on the list will continue to undergo needed cleanup efforts and monitoring to prevent health risks.